Fine Art Wildlife Photography with Wolf Ademeit

Making wildlife photography into fine art photography

I have done black and white photography since my youth. A few months ago, I found my first black and white photographs, 6×6 contact prints, in an old photo box. As a child, I was fascinated by father’s great camera – I think it was a simple Agfa Box 6×6. I used this camera to photograph my friends starting when I was 6 years old. I’ll never forget the miracle of the photo development; with the light of a desk lamp, a glass plate, a negative, and some liquid, it conjured up images on a white sheet of paper.

During my Lithography training, I came into contact with many professional photographers. Among them I found a mentor who taught me the art of photography and the discipline that is necessary for black and white development. If you are shooting with film, the negative is only the first step to getting to the final picture. I used the development process to tailor the look of my final image, so that it met my vision. To this day, this concept still holds true for me. I shoot exclusively in RAW format and I then process the images in Lightroom. I look at the RAW photographs as negatives for me to develop into my final artistic vision.

Why did you choose black and white wildlife photography?

For my wildlife photography series, ANIMALS I chose black and white for artistic, as well as for financial reasons. My intention was to produce a fine art calendar with these images. The cost for a blackened white printed calendar is much cheaper then it is for a CMYK printed calendar. Therefore, the decision to take black and white images was set before I even started to photograph the wildlife photography series. I took every shot with black and white photography in mind and did not care about the colors in the shot. The only things that interested me was the animal and the contrast between the animal and the background.

Your Series ANIMALS took five years to complete, why so long?

Yes, that’s a long time for a project, but wildlife photography is very tedious. You can’t plan the behavior of animals. Sometimes you have to wait a very long time, before you can photograph a specific animal with a special pose. Often animals are inactive, for example sometimes the lions sleep all day and are active only briefly. You have to watch the animals closely to get good photos.

How are you able to achieve studio lighting while shooting in a zoo?

The light – it’s a blessing and curse for every photographer…light is never the way you would like it to be and you need to handle it as it is.

I prefer soft light and shot most of my wildlife photography images under cloudy skies or on rainy days. I also prefer shooting in the early morning or late afternoon with a low sun. The problem is the low light. Most of my pictures appear clam and static, but most of them are action shots, for example in my picture “Sunshine Reggae” it looks like the chimpanzee is relaxing on a tree. In actuality, he held this position for no more then two seconds.

How are you able to capture such perfectly timed images?

With a long exposure time, it is necessary to capture the shot at just the right moment, when the animal’s movement is at it’s peak, but then stops for just a second. My camera, a Sony A77, is able to shoot more then 10 frames per second, but I always work with the lowest continuous shooting mode. I think a photographer should work more like a sniper to capture a picture, and not like someone with a machine gun – creating thousands of worthless pictures.

What tips do you have for wildlife photography?

For my ANIMALS series I used the same techniques I would use for a human portrait, except for the fact that it is not possible instruct a wild animal how to act. Therefore, I have to be patient and just concentrate and wait for the right moment. Sometimes it is very frustrating when nothing happens.

What are some common mistakes you see people making when photographing animals?

I have offered some training classes during the last several years, and I have often found that people put their trust in the camera’s technology, rather than relying on their own instinct for capturing the right moment. They would use continuous capture modes to take up to 30 pictures, but miss most of the right moment because the camera was too busy saving these images. Then they started to check all of these images in the camera display, while the action was still running. A way to move away from this is to set the camera to single shot mode and turn off the automatic picture display for a while. It is not important to see what happened – it’s more important to watch what happens next.

I think a photographer should try to capture the exact right moment – otherwise he should switch to video and dig for the snapshot later.

Some photographers try to get the animals’ attention by making loud noises. If you do so, you capture an animal that looks frightened. I prefer to wait. Most of the time something else gets the animals attention. I captured a polar bear when he smelled the fish that was being used to feed seals nearby. In this case, I chose not to photograph the seals during their feeding, but instead photographed the polar bear in a natural pose when he first smelled the fish.

What animals are the most difficult subjects to photograph?

For my primate series, I spent a lot of time. I had to be very patient and never photographed the primates like paparazzi. I used a right-angle-view-finder to take the images. After a while, I was able to photograph a large spectrum of true emotions; incredible tenderness, fun, sadness, and extreme violence – all this completely unfiltered.

Sometimes it was very emotional for me as the photographer, too. Once I was able to photograph a chimpanzee mother with her newborn baby over several days. At first she always protected the baby with her own body, but some days later she presented it to me like a proud human mother would. Two weeks later the baby died and a friend told me the chimpanzee mother continued to carry the dead baby around for a couple of days. My picture “A Last Kiss” shows the tenderness I had captured during my last visit.

What does your post processing workflow consist of?

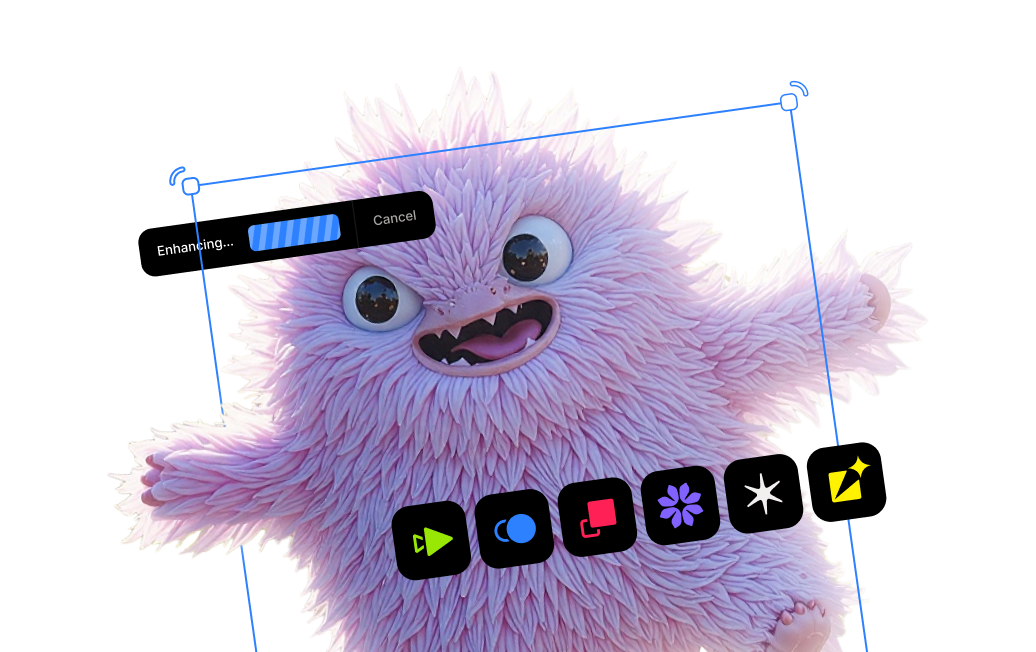

I have been using the Topaz plug-in series for a couple of years as a part of my workflow. For my post processing, I use all Topaz plug-ins. Some of them are truly amazing.

About Wolf Admeit

Wolf Ademeit, born 1954, lives in Moers, Germany. The author prefers calling himself a hobbyist, though his professional life has been always closely connected with this field – he owns an advertising agency and a photo studio. Wolf Ademeit first took interest in photography when studying lithographer’s craft and it’s been his passion since, for more than thirty years now.

It’s Ademeit’s distinctive approach that makes his work stand out of a long row of ever trendy black and white photography adepts or, speaking of his most known series, animalist masters. Unique of the author is his ‘hobbyist’ choice to capture expressive portraits of zoo animals. Rather than focusing on wildlife in their naturally beautiful habitats, Ademeit finds charm and personality in the facial expressions of his subjects alone. Call it ‘animal portraits’, if you wish. More than simply keeping a visual record, the photographer provides an artistic portrayal that is often reserved for human portraiture. Says the author: “Only a few photographers use the photography of animals in zoos as an art form. I think this is a missed opportunity… With my pictures I would like to move the photography of these animals in the focus of the art photography and show photos which are not only purely documentary.”

Ademeit’s incredibly artistic collection of images offers a wide range of emotions, capturing every grimace, ferocious roar, tender kiss, and twinkle in the varied creatures’ eyes, each caught within a second of the animal’s position he sought for. No wonder his highly acclaimed Animals series took 5 years to finish, patience being a part of the author’s talent and mastership.

Check out more of Wolf’s work here: www.wolfademeit.de

.png)

.png)

.png)